The emergence of global value chains (GVCs) in driving manufacturing production has changed the way we view firms and analyse industry and trade data. With the reduction in transport costs and the advances in information and communication technology, firms have fragmented their production process and spread operations and tasks across national borders. Given the paucity of firm data little is known about the participation of African manufacturing firms in GVCs and the impact this has on employment, productivity and exports.

A deeper understanding of African manufacturing firms’ participation in GVCs is becoming increasingly important. The African Continental Free Trade Area aims to boost intra-regional trade in manufactured goods and the development of regional value chains. Rising wages in China have created opportunities for African manufacturing firms to ‘capture’ some of the low-cost labour-intensive activities of GVCs. This is already the case in Ethiopia, where rapid growth in exports has made it the largest sub-Saharan footwear supplier to the United States.

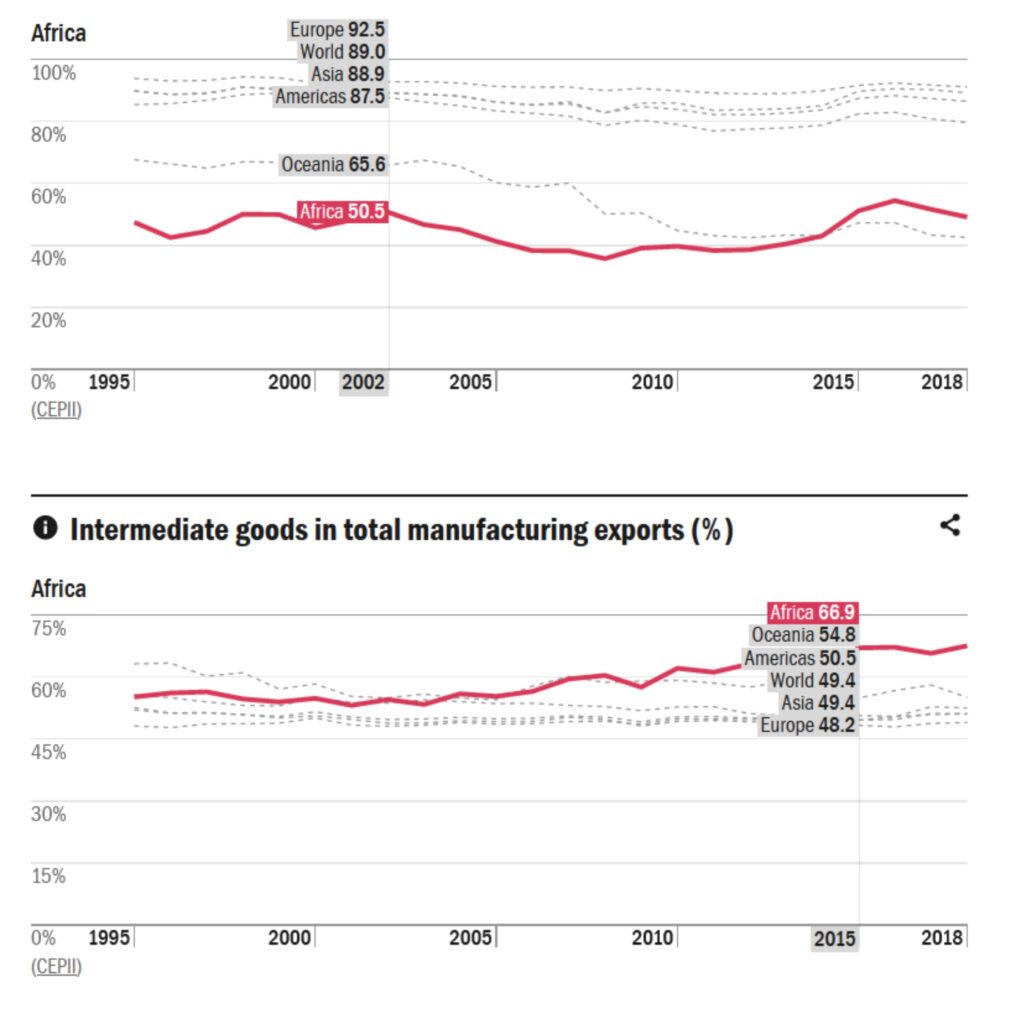

Given the continent’s abundance in natural resources, manufacturing contributes less towards African country exports than many other parts of the world. However, the manufacturing share in exports expanded strongly from 35.5 per cent in 2008 to 54.2 per cent in 2016. A comparatively high and rising share of these manufactured exports consist of intermediate goods. While the bulk of exports are made up of low- and medium-technology intensive products such as metals and food and beverages, there is also evidence that high-technology chemical and automotive products are being exported.

Overall, the aggregate data tells us that African manufacturing exporters are becoming more integrated in global production networks, but mainly as suppliers of upstream intermediate inputs. What do these African manufacturing firms look like and how has their participation in GVCs affected them? Recent research on manufacturing firms in South Africa, Ethiopia, Egypt and Morocco provides some interesting insights.1

One key observation is that firms differ considerably from one another, even if they operate in the same industry. Take, for example, firm productivity as measured by value added per worker. The differences in productivity are often greater between firms operating in the same industry than they are between firms from different industries.

Firms also differ in terms of trade status. The evidence for Africa shows that very few firms engage in export and when they do, they still sell most of their output to the local, not foreign, market. For example, in South Africa, around 19 per cent to 24 per cent of manufacturing firms export their goods, but fewer than 10 per cent of firms export more than half of their output, and the median exporter only exports 4 per cent of its output.2 Exports are also highly concentrated with a few ‘super exporters’ dominating the export bundle.3 This relationship is not unique to South Africa and applies to other African countries as well such as Lesotho, Madagascar, Zambia and others.

The implication is that aggregate trade and production values, even at industry level, can mask huge variations in performance across firms. The trends in the aggregate data generally reflect the performance of large firms that dominate sales, and not necessarily the smaller manufacturing firms.

Policy and research all too often focuses on export performance, while participation in GVCs mostly entails both export and import. The role of imports in production is particularly important for manufacturing firms in Africa. World Bank Enterprise Survey data and other research reveals that over 65 per cent of manufacturing firms in Botswana, Egypt, Ethiopia, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Morocco, Namibia and Zimbabwe participate in either direct or indirect importing. This share is substantially higher than in the U.S. where only 20 per cent of manufacturing firms participate in importing.4 Manufacturing requires access to a broad set of intermediate inputs. What the data reveals is that imports present the only available option for many firms in Africa to access these production inputs.

Access to imported inputs is also crucial for firms that strive to participate in GVCs as exporters. This is revealed in the aggregate data, which indicate that foreign value added is rising as a share of domestic exports in South Africa and Morocco, as has been the case for the world as a whole. Firm-level data corroborates this finding with an average of over 75 per cent of exporters from African countries importing intermediate inputs, either directly or indirectly.5

The characteristics of firms also differ in accordance with their trading status. Evidence for Ethiopia and South Africa reveals that two-way traders (importers-exporters), consistently demonstrate premiums in terms of output, employment, wages and productivity compared to firms that do not trade, or that only export or import. The use of imported intermediate inputs again plays a prominent role in driving these outcomes.6 Take productivity, for example. Productive firms are more likely to engage in exporting and importing given the fixed costs of establishing international supply linkages. However, once they start engaging in trade, imports enable firms to upgrade their technological capabilities through two channels: use of higher quality inputs in the form of new technologies and access to a wider range of complementary inputs.

Both import channels are found to play an important role for manufacturing firms in Africa. In Ethiopia, participating in importing raises a firm’s productivity by 3.5 per cent to 4.9 per cent, with the effect becoming stronger the higher the share of imports in intermediate input costs (up to 22 per cent).7 In South Africa, a key source of productivity gains from importing arises from access to a wider range of complementary imported inputs. For example, a 10 per cent increase in the number of varieties imported by a manufacturing firm in South Africa is associated with a 0.3 per cent increase in productivity.8The use of imports in production, therefore, reinforces productivity gains that have been shown to accrue to African manufacturing firms through exporting.9

The use of imported inputs is also strongly associated with a firm’s export performance. Exporters in South Africa that import tend to have higher export values and to export more products to a wider range of countries. Further, the higher the number of varieties of inputs imported, the greater the diversity of exports in terms of the number of products and destinations. Kenyan exporters of manufactured goods exhibit the same trend.10

The evidence on firms suggests that boosting the integration of African manufacturing firms in foreign markets and GVCs presents an opportunity for countries to increase employment, exports and aggregate productivity. There are several measures that policymakers can implement to enhance this process.

Firstly, industrial policy to facilitate participation in GVCs should not only look at industry-level aggregate data but also consider the diverse characteristics and needs of firms. For example, high trade costs associated with poor transport infrastructure and cumbersome importing and exporting procedures in many African countries are detrimental to GVC participation by manufacturing firms, irrespective of their industry classification. Mitigating these constraints to participation can be expected to generate more participation by firms in exporting from all industries with stronger effects for medium sized firms.

Second, policies that constrain access to imports such as tariffs, import permits and domestic content requirements can hamper export performance and firm productivity growth. Several measures can be implemented to address this problem. For example, high tariffs on intermediate inputs that raise costs for firms can be reduced. Strict rules of origin that impede intra-African trade within the various Regional Economic Communities can be relaxed. Raising port capacity to handle containers will boost exports directly and indirectly by improving access to imported manufactured inputs.

Thirdly, policymakers and researchers need to be cautious in assuming that industry aggregates reflect average firm performance. Very high concentration in exporting implies that the aggregate data may largely reflect the performance of a few large firms. Firm-level analysis, including interviews with firm managers, are required to understand some of the dynamics behind aggregate-level trends in the data.

High trade costs in many African countries are detrimental to GVC participation for manufacturing firms, irrespective of their industry classification.

References

- For Ethiopia, see Abreha, Kaleb Girma. (2019) Importing and Firm Productivity in Ethiopian Manufacturing. The World Bank Economic Review 33(3), 772-792. For Egypt and Morocco, see Del Prete, Davide; Giovannetti, Giorgia and Marvasi, Enrico. (2017) Global Value Chains Participation and Productivity Gains for North African Firms. Review of World Economics 153(4), 675-701. For South Africa, see Edwards, Lawrence; Sanfilippo, Marco and Sundaram, Asha. (2018) Importing and firm export performance: New evidence from South Africa. South African Journal of Economics 86(S1), 79-95, and Edwards, Lawrence, Sanfilippo, Marco and Sundaram, Asha. (forthcoming) Importing and productivity: An analysis of South African manufacturing firms, forthcoming in Review of Industrial Organisation.

- Matthee, Marianne; Rankin, Neil; Webb, Tasha and Bezuidenhout, Carli. (2018) Understanding Manufactured Exporters at the Firm‐Level: New Insights from Using SARS Administrative Data. South African Journal of Economics 86(S1), 96-119.

- According to transaction level trade data for the period 2009-2013, the top 1 per cent of trading firms account for over 75 per cent of the total value of exports.

- Bernard, Andrew B.; Jensen, J. Bradford; Redding, Stephen J. and Schott, Peter K. (2018) Global Firms. Journal of Economic Literature56(2), 565–619.

- This holds for Botswana, Lesotho, Egypt, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mozambique, Morocco, Malawi, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

- See Edwards et al. (2018) for South Africa, Abreha (2019) for Ethiopia and Del Prete et al. (2017) for Egypt and Morocco.

- Abreha, Kaleb Girma. (2019) Importing and Firm Productivity in Ethiopian Manufacturing. The World Bank Economic Review 33(3), 772-792.

- Edwards et al. (forthcoming). Variety is measured as the number of product-origin combinations imported by the firm. For example, if an apparel firm imports a given type of fabric (measured at the 6-digit level of the Harmonized System product classification) from five countries, it counts as five varieties. A strong positive association is also found between firm productivity and the average number of products imported per source (scope) and the average number of sources per product (scale).

- See Bigsten, Arne; Collier, Paul; Dercon, Stefan; Fafchamps, Marcel; Gauthier, Bernard; Gunning, Jan Willem; Oduro, Abena; Oostendorp, Remco; Pattillo, Catherine; Söderbom, Måns; Teal, Francis and Zeufack, Albert. (2004) Do African Manufacturing Firms Learn from Exporting? Journal of Development Studies 40(3), 115-141. They find significant efficiency gains through learning from exporting in African manufacturing firms in Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya and Zimbabwe.

- See Chacha, Peter Wankuru. (2017) Firm Level Export Dynamics and Market Access Costs: Evidence from Kenya. PhD in Economics Dissertation, University of Cape Town. In Kenya, a 10 per cent increase in imported varieties by an exporter is associated with a 1.4 per cent increase in the number of products exported and a 0.6 per cent increase in the number of countries exported to.

Recent Comments